Helliwell v Entwistle

CORRECTING THE NARRATIVE

Isabella Cox

10/5/20252 min read

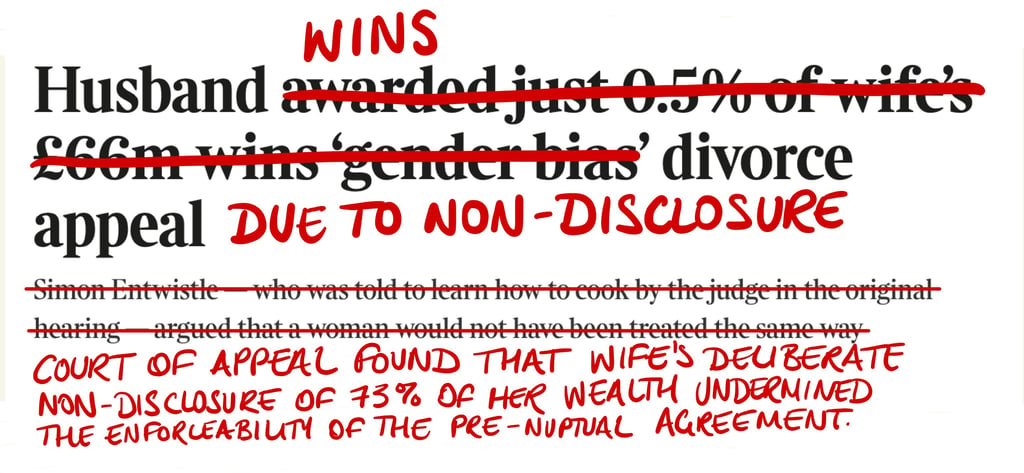

Recent headlines have erroneously positioned the Court of Appeal’s decision in Helliwell v Entwistle [2025] EWCA Civ 1055 as a victory against gender discrimination in the family courts. It wasn’t. This appeal turned on the enforceability of a pre-nuptial agreement (PNA) in the face of deliberate non-disclosure of 73% of the wife’s wealth.

Context and the Preceding Judgment

The dispute concerned the financial settlement awarded to Mr Entwistle on the breakdown of his three-year marriage to Ms Helliwell. The parties had a ‘drop-hands’ PNA which provided that, in the event ofdivorce, they would retain their own assets and neither would make a claim on the other in any jurisdiction.

Despite these terms, following separation, the husband sought a financial order on the basis that the PNA should not be given effect. The central issue was whether the wife’s non-disclosure of assets totalling £47.9 million vitiated the PNA.

The wife was the wealthier party, with assets in excess of £60 million. The husband had net assets of £850,000, with c.£500,000 tied up in property and not readily liquid.

Per Radmacher v Granatino, a PNA will be given effect, provided both parties entered into it freely, with full understanding of its implications, unless it would be unfair to do so.

The wife’s position was that the marriage was short and childless; the husband had entered into the PNA freely, with legal advice and fully understood its consequences. She accepted that she had significantly understated the value of her wealth, but argued the husband was aware he was marrying a wealthy woman and the non-disclosure did not undermine the validity of the PNA.

Conversely, the husband argued that the PNA should be vitiated on the basis of material non-disclosure and that he had been persuaded to enter into the PNA as a concession to the wife’s father.

Francis J gave decisive weight to the agreement, finding no reason to depart from the parties’ initial contractual position. Despite this, he ordered the wife to pay a £400,000 lump sum to the husband to meet his needs.

The husband’s financial claims included £36,000 for flights and £26,000 for a meal plan. The latter claim, which the husband made on the basis that he “can’t even cook an omelette”, was dismissed with Francis J’s retort: “‘Learn’ (…) You do not need to be a master chef to learn how to eat reasonably well.” This claim attracted disproportionate media attention, which underscores Francis J’s broader critique:

“I do suggest to lawyers who prepare these budgets that if you put something in the schedule which is absurd, it can discolour the whole case.”

The husband appealed this decision and claimed gender bias, contending that Francis J’s award afforded him markedly less than would have been granted to a wife in similar circumstances.

The Appeal

The Court of Appeal allowed the husband’s appeal, holding that Francis J had erred in concluding that deliberate non-disclosure did not vitiate the PNA. The case was remitted to be reheard in the High Court with emphasis on reassessment of the husband’s needs.

No finding of gender bias was made.

A Note on Appeal

For fuller treatment of the complexities surrounding fraudulent non-disclosure in PNAs, Sir Nicholas Mostyn’s article in the Financial Remedies Journal offers a detailed critique of the Court of Appeal’s reasoning. He questions whether the wife’s conduct was truly ‘fraudulent’ within the established triad of dishonesty, gain and corresponding detriment, and whether the Court was right to foreclose further fact-finding on materiality. He suggests there may be arguable grounds for the wife to seek permission to appeal to the Supreme Court.

Veritas Vincit.

Truth Prevails.

Contact Us

veritasvincit.lp@gmail.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.