Captivity of Expression: India’s Suppression of Dissidents

PERSPECTIVES

M. K. Singh

10/5/20256 min read

India: the world’s largest democracy. It would be reasonable to believe that the freedom of expression would be a pillar of this functional democracy, wouldn’t it?

When India gained its independence in 1947 following brutal colonialist oppression, it was the government’s intention to bring forth free speech and allow the people to hold and express their own opinion. 1950 brought about the Indian Constitution, which pledged to protect people’s freedom as a fundamental part of its own national identity. However, even though this is stated on paper, in reality, this ‘dream’ often falls short.

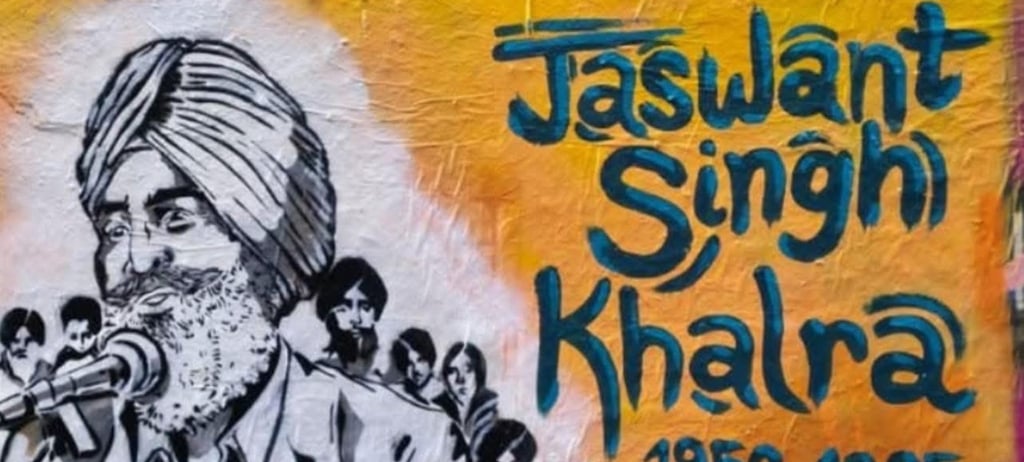

From the abduction and subsequent murder of Jaswant Singh Khalra, to the curbing of Amritpal’s ability to communicate his views, India has resorted to heavy-handed approaches to suppress its people, on numerous different occasions. These events then bring forth the question, is India really adhering to Article 19 of its own constitution? Or has the government taken a more tyrannical approach when dealing with people’s free will to share their opinion? Through this article, I set out to examine whether the government is truly is trying to protect its sovereignty and security (Constitution of India, Article 19, 1950), or whether the government is forcibly diminishing free speech, or if the government is only trying to hinder opinions which are not relating to those of the people in government. Although only Sikh dissidents are mentioned as case examples in this article, it is not to say that there are not numerous other cases from a variety of contextual backgrounds, where dissidents are supressed by the government in relation to their views.

Article 19(1)(a) guarantees citizens the right to freedom of speech and expression, which outlines the original intent to allow for open debate, as part of a democratic society. (Constitution of India, Article 19, 1950). From this, it can be inferred that the government may have originally intended people to express their opinion, however this is short lived. Within the same article, the next subsection (article 19(2)) places ‘reasonable restrictions’ on the freedom of speech, while not uncommon for qualified human rights like the freedom of speech, has resulted in increasing interference with the right as the restrictions have been abused by the government. This is in direct violation of the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights (‘ICCPR’), a cornerstone international treaty which was made for the protection of individual and political rights. Although a signatory to the ICCPR, India has hampered the protections under this treaty by lodging a reservation against it, only permitting the freedom of expression within the pre-existing parameters of its constitution. Nonetheless, the freedom of expression is safeguarded by customary international law, and India remains obligated to uphold it, subject to legitimate restrictions, of course – ‘legitimate’ being the key word.

India's usage of Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code (sedition), which was initially drafted during colonial authority, is notably controversial (Indian penal code, 1870). Despite the Supreme Court's limited application to incitement of violence or public disruption, charges for mere criticism continue. The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act offers broad detention authorities and frequently targets activists, journalists, and protest organizers without prompt hearings (The Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967). The Information Technology Act allows the government to take down internet information and monitor message origins, but its ambiguous language can lead to arbitrary digital censorship (information Technology act, 2000). In all of this different legislation, its clear that there should be no room for the government to put in anti- expression legislation. However its still clear that despite there being legislation to protect the people’s expression, there is still controversy in the government’s application of this legislation when it comes to supressing people’s opinion.

A key example of the government actively supressing dissidents is the case of Jaswant Singh Khalra, and his abduction and subsequent murder, clearly showing the consequences of unchecked state power. Khalra, a bank manager, took it upon himself to collect data on all the people that had been abducted or subjected to enforced disappearances. He documented cremation records, and uncovered thousands who had been murdered and subsequently cremated without informing the families. On the 6 September 1995, Khalra was abducted by police (India a Mockery of justice, 1998). It took till July 1996 for the CBI to present the investigation report to the supreme court, which outlined that 9 police officers were involved in Khalra’s abduction, and then vouched for their prosecution (Amnesty International, 1998). It was never confirmed where his body was. His abduction and murder provide clear evidence of the abuse of power by agents of the state, which in this case was used to suppress someone who tried to bring forth justice for many people who illegitimately lost their lives. This suppression reignites the debate as to whether there is freedom of speech given to all citizens, or if it is just restricted only for those who blindly follow the state. Cases like this ultimately raises concerns whether article 19 of the Indian constitution truly upholds democratic values and whether there is any true intention of giving people the right of speech and the freedom to express their opinion. As is illustrated in this case, Khalra only intended to bring light to the many people that had arbitrarily gone missing, and even that led to his own capture and death.

A recent example of this same tyrannical approach can be found with the Indian State’s response to Amritpal Singh. In his case, he has attracted legal and media attention due to his supposed extremist activity in Punjab (BBC, 23 April 2023.) The government accused Amritpal of both terrorist activities and the assault and murder of a police officer; however, there is no evidence to confirm these accusations. Amritpal was subsequently arrested and detained after a manhunt, in which he was captured. As he was ‘arrested under the stringent National Security Act (NSA)’ he can be detained for up to a year without being charged (BBC, 2023) However, it was Amritpal’s Sikh separatist state ideology in favour of ‘Khalistan’ that led to the government seeing him as a threat, resulting with him being dealt with in such a way. Measures were also taken to ensure that the public were also hindered digitally. The government decided to cut off the internet service to try to find Amritpal during the manhunt. (NBC News, 2023.) This manipulation of digital media, and the captivation of the expression of the people of India, Punjab in particular, is clearly the misuse of legal legislation for government benefit, as the digital cut-off was to try to cut down the support of the supposed ‘terrorist’, however its not clear why he was deemed as a national threat and why they took such measures to try to capture him, particularly as there was no clear evidence was found in these accusations against Amritpal Singh. In this case, the detention demonstrates how the state continues to straddle the fine line between public order and civil liabilities.

There are decades between the two cases, yet we can still see clear continuity and potential evolution in India’s approach towards handing dissidents. The continuity lies in the clear prejudice when the Indian Government applies article 19(2), invoking it usually for self-serving purposes. The evolution comes from the judicial scrutiny and the use of digital tools to mediate enforcement and hinder the expression of the public. The cases also underscore the importance of transparency within the procedures and the adherence to pre-existing human right norms which have been clear in the article 19(1)(a) and the ICCPR, as in these two situations, it is clear that India has taken steps to ensure that their own legislation can tamper with the freedom of expression under the guise of ‘national security’ and ‘government protection’.

To conclude, there have been numerous occasions where the Indian government has maliciously used legislation to prevent people’s freedom of speech. The two cases that I have put forward have also clearly show that even over a notable span of time, the Indian government still hasn’t changed its approach towards dissidents and instead has developed their methods of restricting their expression.

This systemic pattern of suppression is deeply disturbing, particularly as the freedom of expression was never created to protect the views of the majority, but rather it exists to protect the views of those in the minority, in particular dissidents. Where this human right is interfered with to such an extent, it renders the freedom of expression to the status of a human right without teeth, ultimately captive to the constitution that subjugates it.

References:

Amnesty International (1998) A mockery of justice: The case concerning the ‘disappearance’ of human rights defender Jaswant Singh Khalra severely undermined. Available at: https://www.amnesty.org/fr/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/asa200071998en.pdf (Accessed: 3 October 2025).

Article 19 (2023) India: Freedom of expression under threat. London: Article 19. Available at: https://www.constitutionofindia.net/articles/article-19-protection-of-certain-rights-regarding-freedom-of-speech-etc/ (Accessed: 3 October 2025).

BBC News (2023) India news. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-india-65063620 (Accessed: 3 October 2025).

University of Minnesota Human Rights Library (no date) Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967. Available at: https://hrlibrary.umn.edu/research/unlawfulactivitiesact-1967.html (Accessed: 3 October 2025).

India Code (no date) Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 – Section 37. Available at: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/show-data?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=133#:~:text=%2D%2DWhoever%20by%20words%2C%20either,%5Bimprisonment%20for%20life%5D%2C%20to (Accessed: 3 October 2025).

Image: Bethany Cherry; @why_knot_art

Veritas Vincit.

Truth Prevails.

Contact Us

veritasvincit.lp@gmail.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.